- If S sees x, then x exists

- Seeing is an intentional state

- Every intentional state is such that its intentional object is incomplete

- Nothing that exists is incomplete.

- If S veridically sees x, then x exists

- Veridical seeing is an intentional state

- Every intentional state is such that its intentional object is incomplete

- Nothing that exists is incomplete.

The nice answer is to say, No, the tetrad is perfectly consistent, but there are no intentional objects. Another answer is to reaffirm the consistency of the tetrad but assert that intentional objects are non-existent. This is presumably the Meinongian route which Bill has repeatedly scorned, though Ed Ockham regards him as a Meinongian in denial. I propose to go with the nice answer. There is obviously something very fishy about (3). It's trying to say something interesting about the aspectuality of intentional mental states, but the language is not quite right. It is, as it were, ontologically over-committing. Is there a way of conveying the sense of (3) without using the language of objects?

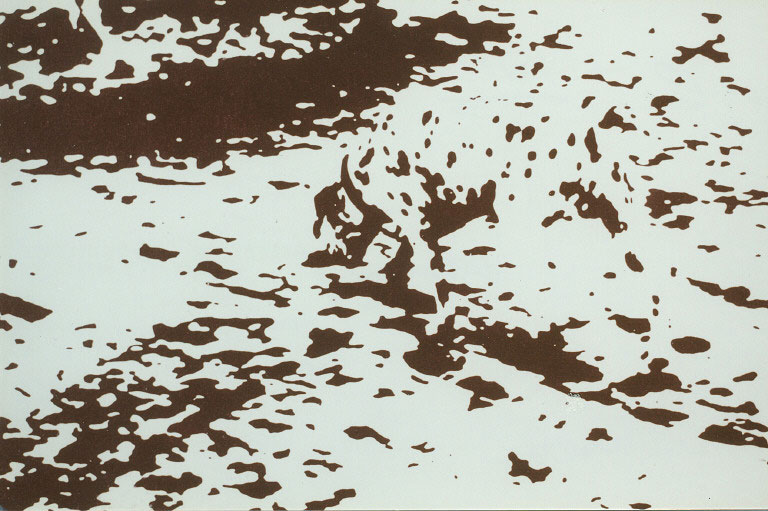

When we look at a thing or think about a thing, that which is manifestly incomplete is our knowledge of that thing. Perhaps I should use a term more 'truth-neutral' than 'knowledge', but it seems appropriate. When the drunk sees pink elephants he knows they are pink. When we look at a thing or think about a thing what is 'before our mind', or better, 'in our mind' is knowledge of that thing. Here is a well-known image:

On first seeing this picture it may be that all we have in mind is the thought that there are patches of dark and pale. Arguably this state is not intentional. Then, perhaps after a little hinting, quite suddenly what comes to mind is the thought that there is a dalmation dog, standing, its left flank turned away from us, and its nose to the ground. There is little more that can be said, especially if we close our eyes and try to recall the scene. We know there is a dog, but we know relatively little about it.

Why then would the philosopher fall into talking of 'incomplete objects'? Perhaps through a wish to be true to the visual experience? There are but two possible experiences here: the patches of light and dark, and the dalmation dog. To speak of an 'incomplete dog' fails to capture the experience, as we have seen. Besides leading to absurdity, as our revised aporia shows. Perhaps to remain neutral as to whether visual experience gives us knowledge of external objects? Possibly, but to describe the experience in terms of objects, complete or otherwise, is tacitly to presuppose that there are such things. If visual experience were merely of patches of light and dark we could never grasp the concept 'object'. Just as the experience itself is dual, there are two alternatives in describing it: the object-free and the object-saturated, the non-intentional and the intentional. There is no middle ground.

Intentional states have objects in this sense. They are states in which thoughts having the following form occur: There is an object; it has property P1, P2, ... and it enters into relations R1, R2, ... with other objects. When we reflect on this intentional state we recognise that the set of thoughts it contains is incomplete---no object is fully knowable to a finite mind. Furthermore, these thoughts need not be true.

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.